Techniques

Observation is the key to all of Patrick's work as an artist and sculptor. Studying plants and insects in his childhood, he would make little sketches and diagrams long before he ever possessed a camera, and this was encouraged during his biology classes at school and college. When 'on location' now whether at home in Ireland or in remote parts of the world, it is his highly detailed and measured pencil drawings that are key to his research. They, together with detailed notes of the habitat and the associated fauna and flora, and colour calibrations taken direct from the growing plants - and backed up by photographs- provide the information from which a sculpture or a watercolour painting will be made on return to his studio, or perhaps decades later.

Sculptures

Much has been written about the methods that Patrick has used in the making of his sculptures, inventing or re-inventing techniques that enable him to achieve an extraordinary degree of detail in portraying his wildlife subjects, as well as the total integrity of his chosen medium. This choice of ceramic – and hard-paste porcelain in particular – as his medium for sculpting unique and original three-dimensional works, gives him a sympathy with some of the earliest inventors and designers in Asia and Europe. He has continually developed his hand-building of complex structures – reserving the use of moulds merely for the casting the shapes of his small “Secret Garden” capsules.

Much has been written about the methods that Patrick has used in the making of his sculptures, inventing or re-inventing techniques that enable him to achieve an extraordinary degree of detail in portraying his wildlife subjects, as well as the total integrity of his chosen medium. This choice of ceramic – and hard-paste porcelain in particular – as his medium for sculpting unique and original three-dimensional works, gives him a sympathy with some of the earliest inventors and designers in Asia and Europe. He has continually developed his hand-building of complex structures – reserving the use of moulds merely for the casting the shapes of his small “Secret Garden” capsules.

For his early ceramic models of traction engines and vintage cars, he used a white earthenware clay which fired to 1050°C and was decorated with colour glazes fired to around 800°C. Earthenware retains its shape with little shrinkage, which proved ideal for mechanical subjects, but is too brittle to allow very fine detail. Having honed his ceramic skills and his observation on what to him were totally unfamiliar subjects, Patrick wanted to apply himself to portraying the delicate flowers and butterflies that were his real interest. He realised that earthenware was too crude and opaque for this purpose, so he experimented with bone china and felspathic porcelain, and finally settled on a proprietary variety of the latter. Based upon the analysis of a fine and highly modellable clay originally mined in one particular location in Kyushu, Japan, he then refined it further by repeated screening, with the result that it will permit an extraordinary fidelity of tiny detail, a translucence that nears transparence when fired, and has a shear strength of more than 10,000 lbs per sq.in.

For his early ceramic models of traction engines and vintage cars, he used a white earthenware clay which fired to 1050°C and was decorated with colour glazes fired to around 800°C. Earthenware retains its shape with little shrinkage, which proved ideal for mechanical subjects, but is too brittle to allow very fine detail. Having honed his ceramic skills and his observation on what to him were totally unfamiliar subjects, Patrick wanted to apply himself to portraying the delicate flowers and butterflies that were his real interest. He realised that earthenware was too crude and opaque for this purpose, so he experimented with bone china and felspathic porcelain, and finally settled on a proprietary variety of the latter. Based upon the analysis of a fine and highly modellable clay originally mined in one particular location in Kyushu, Japan, he then refined it further by repeated screening, with the result that it will permit an extraordinary fidelity of tiny detail, a translucence that nears transparence when fired, and has a shear strength of more than 10,000 lbs per sq.in.

Working to less than one millimetre thickness for petals, leaves and butterfly wings, Patrick found that his structures would not only shrink by one-eighth, but would soften and collapse during the near 1300°C porcelain firing. He solved this by propping every part of the sculpture with a material developed to insulate the space-shuttle during re-entry. Each sculpture is complete in every physical detail when it undergoes its first firing (1000ºC), is then propped for the high porcelain fire, after which it is scrubbed clean of any dust, sprayed with transparent glaze for the glost firing to 1170°C. It comes out now white, shiny, strong and magically translucent and true porcelain. Most times, he will then handpaint every part of the sculpture with colour glazes that were exactly matched to the living plants and insects when he made his original field drawings. Using up to sixteen different silicates and oxides, he has formulated more than 4,500 different shades of enamel glazes over the years.

Working to less than one millimetre thickness for petals, leaves and butterfly wings, Patrick found that his structures would not only shrink by one-eighth, but would soften and collapse during the near 1300°C porcelain firing. He solved this by propping every part of the sculpture with a material developed to insulate the space-shuttle during re-entry. Each sculpture is complete in every physical detail when it undergoes its first firing (1000ºC), is then propped for the high porcelain fire, after which it is scrubbed clean of any dust, sprayed with transparent glaze for the glost firing to 1170°C. It comes out now white, shiny, strong and magically translucent and true porcelain. Most times, he will then handpaint every part of the sculpture with colour glazes that were exactly matched to the living plants and insects when he made his original field drawings. Using up to sixteen different silicates and oxides, he has formulated more than 4,500 different shades of enamel glazes over the years.

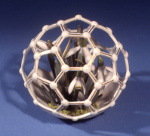

In his various series of 'Secret Garden' sculptures, he expanded the principle of pierced porcelain to encapsulate tiny sculptures. Earlier, he had unwittingly re-invented the supremely difficult technique of pâte-sur-pâte – previously perfected in the late 19th. Century by Mark Louis Solon and others at Sèvres in France and at Minton in England. It involves the most delicate painting in white porcelain clay slip onto a coloured porcelain ground, and takes advantage of the translucence of the former.

Watercolours

Patrick still vividly remembers his first watercolour lessons with Miss Ogle, when he was just nine years old, and the pleasure of making simple patterns of brush strokes. Later schooling sadly discouraged his interest in art, but in his career as a sculptor, he gradually used a little watercolour to enhance his pencil drawings. In 1994, he exhibited some of these coloured drawings alongside his porcelain sculptures at the Royal Botanic Gardens, at Kew's Wakehurst Place in Sussex. Encouraged by the reaction, he included ten large watercolours of wildflowers from around the world in his major exhibition at the National Botanic Gardens in Dublin in 2002, and again at Fota House in Cork in 2004.

Many commissions followed and he is now engaged in several long-term projects, including one to produce a series of paintings of the wild flowers of California, for the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden.

In the composition of his paintings, Patrick adopts the same principles as have guided his sculpture designs over the years, but with the added advantage of allowing his butterflies to actually be on the wing, and his flowers to be subtended on the most delicate of stems. His painting technique draws on his study of early Chinese watercolour scrolls, using fine pen work and high quality, lightfast paints on heavy, hot-pressed, acid-free watercolour paper. His preparatory drawings are made and re-made until judged suitable to transfer to the paper. Sable brushes and a collection of various Chinese brushes are used, and great attention is paid to the quality of the water used.

Crystal

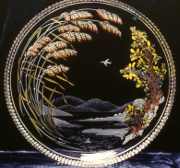

If watercolours gave Patrick's butterflies freedom to roam, then his occasional ventures into the realm of engraved and enamelled lead crystal glass allowed spiders to spin their webs amongst stems of his flowers. Few artists had worked on crystal using both engraving and fired enamel colours since the 1790's, mainly because of the risk of deformation of the glass when being heated in the kiln to anneal the colours into the surface. Patrick decorated a number of crystal platters and vases that had been blown for him in Ireland and England – first applying and firing the colours, and then diamond-wheel and diamond-point engraving the rest of the design on the cold glass. His favourite pieces have been executed using large, naturally-fractured chunks of full-lead crystal glass, whose facets reflect and refract his tiny engravings, enlarging them, reducing them, and even reversing them as the piece turns.

If watercolours gave Patrick's butterflies freedom to roam, then his occasional ventures into the realm of engraved and enamelled lead crystal glass allowed spiders to spin their webs amongst stems of his flowers. Few artists had worked on crystal using both engraving and fired enamel colours since the 1790's, mainly because of the risk of deformation of the glass when being heated in the kiln to anneal the colours into the surface. Patrick decorated a number of crystal platters and vases that had been blown for him in Ireland and England – first applying and firing the colours, and then diamond-wheel and diamond-point engraving the rest of the design on the cold glass. His favourite pieces have been executed using large, naturally-fractured chunks of full-lead crystal glass, whose facets reflect and refract his tiny engravings, enlarging them, reducing them, and even reversing them as the piece turns.